By now, the New Year’s rush at the gym is long behind us. The “new year, new you” enthusiasm has worn off like the screen printing on a T-shirt from 1995. What started as an ambitious drive toward a fitter future has, for many, dwindled to basically nothing.

The drop-off is real.

I don’t want to say that “how to stay motivated” is the age-old fitness question. That sounds cliche, and fitness being an individualized pursuit (detached from, say, military training) seems too modern a phenomenon to call anything about it “age-old”. But we know that it’s hard to start a new fitness routine — and sticking with a fitness routine is just as challenging, if not harder.

This is true for both sexes. According to the United Health Foundation, in the U.S., only 20.8 percent of women and 25.2 percent of men met the federal physical activity guidelines in the past 30 days. Meanwhile, more than a quarter of women (26.5 percent) and 21.2 percent of men reported that they didn’t engage in any physical activity outside their regular jobs.

These low levels of physical activity represent a crisis. Not just of physical fitness, but of physical health.

While it’s true that a myriad of systemic problems drive low physical activity and that there’s no single solution to the United States’ physical fitness crisis, one key to changing these stats is motivation, or the desire to be physically active.

There’s a lot to say about motivation (hence, this series), but the first thing to know is: motivation is not immutable. We can shape our motivation, develop new forms of motivation, and choose exercise elements and routines that drive greater motivation. If motivation is what’s holding you back from a consistent exercise routine, you can take agency, choose a fitness regimen that aligns with your values, and shift your motivations so they’re more likely to sustain you over the long term.

You may not be able to change larger systemic problems that make it harder for the masses to get active, but you can take small, practical steps to make staying active easier for yourself (and, perhaps, share what you’ve learned with others).

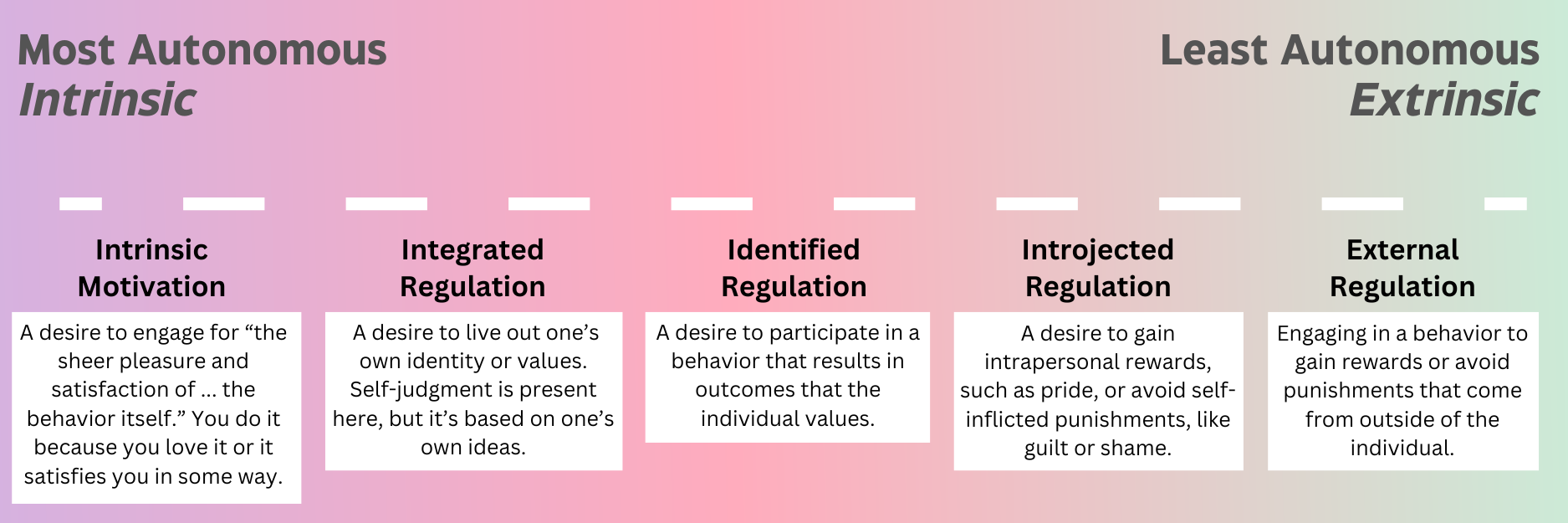

To understand how, let’s take a look at Self-Determination Theory. Self-Determination Theory, or SDT, is an evidence-based understanding of human motivation that pops up all over exercise motivation research. SDT charts human motivation along a continuum based on degrees of autonomy (or self-determination).1

The more autonomous their motivation, the more self-driven a person is. They don’t need a host of outside influences convincing them to do something. They do things because they want to. (Of course, a person can be self-driven in one area of life, but not another area. You might be highly self-motivated to go to the theater or create art, but have no intrinsic motivation for exercise.)

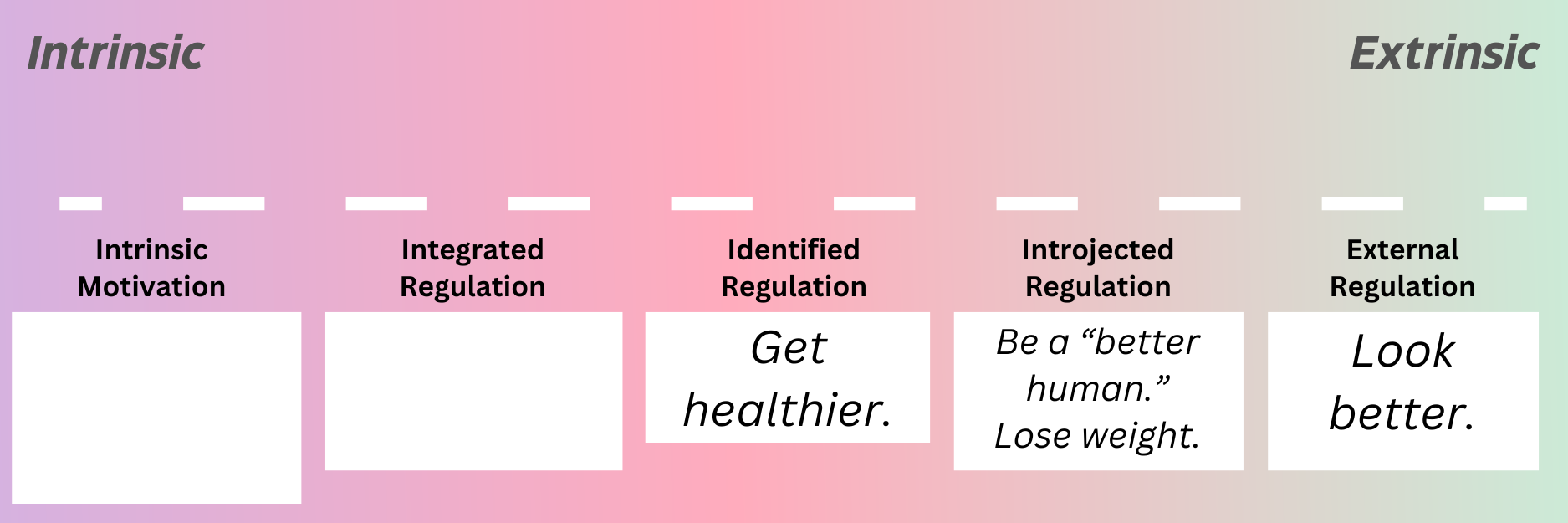

SDT breaks down motivation into the following categories, from most autonomous to least autonomous:

At the least autonomous end of the continuum, people are motivated by gaining external rewards or avoiding external punishments. Toward the center of the continuum, we find motivations driven by external outcomes that are valued by the individual. Meanwhile, the most autonomous, most internal motivation is engaging in something for “the sheer pleasure and satisfaction” of the behavior itself.

Take a second and consider that line-up of motivations. What types of motivations do you think drive people to go to the gym after New Year’s?

Almost always, external motivations. This is particularly true of women: In studies looking at exercise motivation, researchers have found that women tend to exercise for external reasons, while men are more likely to engage in physical exercise for intrinsic reasons.23

External motivations aren’t necessarily bad. Being healthier is a worthy goal, and some people need to lose weight for the good of their health. But external motivations aren’t enough to keep people consistent in exercising.

What is? Internal, or intrinsic, motivation.

Multiple studies over decades have found a strong association between intrinsic motivation and exercise adherence, or sticking to an exercise routine. Sometimes, this intrinsic motivation is there when the person starts their exercise routine; sometimes, it develops as they engage in exercise over a series of weeks or months. But generally, if a person maintains an exercise routine over an extended period of time, it’s because they are self-motivated to exercise.4567

Take a moment and consider your own exercise motivations. Do you want to exercise for external reasons, like health, appearance, or ability? How about for social reasons? Does exercising give you an internal sense of pride or win external respect from others? Do you want to exercise so you can achieve a new feat? Is working out part of your identity, your sense of self? Is it something you enjoy and look forward to?

As you consider your own motivations, check off where they fall on the SDT continuum.

Are you missing any types of motivation?

If you’ve struggled to establish a consistent fitness routine, my guess is you’re probably missing motivations on the more internal end of the continuum.8 If that’s the case, don’t worry. The next few editions of Women’s Barbell Club are going to help you change that.

Because here’s what I’m convinced of:

If intrinsic motivation is highly correlated with sticking to an exercise routine and if most of us have an abundance of external motivation, but basically no intrinsic motivation, then it’s likely that if we — individually and collectively — could develop more intrinsic motivation to exercise, more of us would stick with a fitness routine over time — and reap the benefits of physical activity.

TL;DR: If you’re lacking both intrinsic motivation and consistency with an exercise program, develop your intrinsic motivation and the consistency may come with it.

Stay tuned for upcoming installments of the motivation series. In a few weeks, I’m releasing an article on what I think is the most impactful internal motivator — and I’m pumped to share it with you.

All quotations related to Self-Determination Theory are from this paper: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1479-5868-7-7

Will there be exceptions to this? Yes. But we’re focusing on what we can control. And we can’t always control or change external factors, like the ability to afford a gym membership, time to work out, or spousal support.

Excited for this series! I’ve rarely been one to commit to exercise but I’m one year and three months into a consistent powerlifting/weight lifting routine. It’s 100% been because it’s a satisfying workout with tangible results. In the lifting community I’m a part of, it values getting stronger and puts less focus on looks. Having strength to do things I couldn’t do before and knowing it will serve me as I get older is very motivating.