Pippi Longstocking is the strongwoman we didn’t know we needed

The world's strongest girl has a message for the rest of us.

“And now, ladies and gentlemen, I have a very special invitation for you. Who will challenge the Mighty Adolf in a wrestling match? Which of you dares to try his strength against the World’s Strongest Man?”

…

“I can,” said Pippi, “but I think it would be too bad to, because he looks nice.”

“On, no, you couldn’t,” said Annika, “he’s the strongest man in the world.”

“Man, yes,” said Pippi, “but I am the strongest girl in the world, remember that.”

~ “Pippi Goes to the Circus,” from Pippi Longstocking by Astrid Lindgren,

translated by Florence Lamborn

The Saturday after Thanksgiving, I read the entire first book of the Pippi Longstocking series to my nieces. We giggled as Pippi slept with her head under the blankets and her feet on the pillow, befriended two burglars who thought they could easily rob a girl living alone, and started a house-climbing game of tag with police officers who’d come to take her to a children’s home.

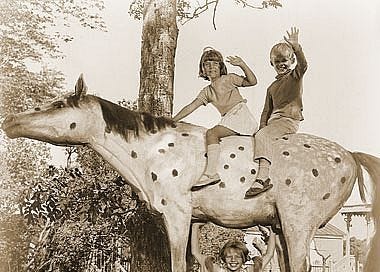

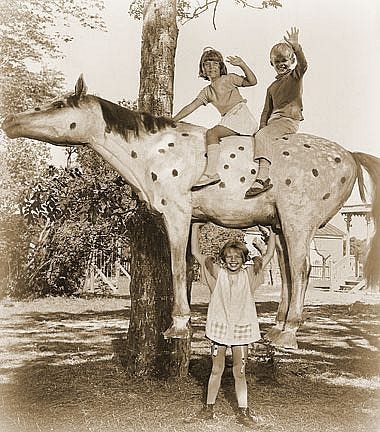

The throwaway detail of Pippi lifting her horse — on and off the porch or into the kitchen for her birthday party — nearly escaped our notice. Of course a girl with red braids sticking straight out of her head who lives alone in a house surrounded by a tangled garden with a monkey called Mr. Nilsson, a chest full of gold pieces, and no grownups to tell her when to go to bed — of course such a girl would also have logic-defying strength. Why blink twice?

Strength and courage are defining features of Pippi’s character. She stands up to bullies of all ages, isn’t intimidated by parents or teachers or circus ringmasters, and despite the fact that she’s very much on her own, she’s not troubled by this. She’s too busy with all the things she’s going to do and try and find.

Her physical strength backs her up. It’s because of her physical strength that she can lift that gigantic circus strongman over her head like a trophy and put bullies in a tree.

In some ways, Pippi Longstocking’s strength is just another idiosyncrasy of a character who’s all quirks. But it’s also an attribute that speaks to the fantasies of the book’s young audience.

At some point in our childhoods, most of us were confronted by our own weakness. For me, it was on the playground, where my spaghetti arms weren’t strong enough to swing on the monkey bars. For others, it may have been in a sport setting, in the face of illness, or in a physical confrontation with a bully — at recess or even at home. Some of these experiences were profoundly disheartening, while others we just shrugged at or were annoyed by. But all of them served to show us our own limitations, our relative powerlessness.

What would it be like to be a fearless, headstrong little girl living alone with all the money necessary to buy whatever she wants and needs? What would it be like to be that girl and also not fear physical harm because she’s fast and strong and spry enough to escape the people who want to harm her?

What would it be like to be able to pick up a horse?

When author Astrid Lindgren first imagined Pippi Longstocking, it was to entertain her daughter who was sick in bed. World War Two was raging on the European continent, and Lindgren, safe in neutral Sweden, was caught between the existential terror of the not-too-distant war and the mundane normalcy of her everyday life.

“Pippi was a stroke of inspiration, not a carefully considered character from the start,” Lindgren said in a December 1967 interview with the Svenska Dagbladet, decades after her character took the world by storm. “Although, yes, she was a little Superman right from the word go—strong, rich, and independent.”1

Taking inspiration from the Man of Steel, as well as characters like Anne of Green Gables, Lindgren created an individual who had what both kids and adults dreamed of: independence, freedom, power. “Thanks to her superhuman physical strength and various other circumstances, she is completely independent of adults and lives her life exactly as it suits her,” Lindgren wrote in a letter on April 27, 1944.

It’s not too far a leap to say that the Swedish supergirl was born from Lindgren’s own feelings of helplessness, particularly in the face of a war that her country was not fighting but was vulnerable to.

Pippi may not have been engaging in battles on the written page, but her self-possession in the face of various grownups — including the intentionally named “Schtrong Adolf” (“mighty Adolf” in some translations) in “Pippi Goes to the Circus” — reflects a fantasy that many of us still hold that we will stand up for ourselves and others in the face of powerful bullies. And that we will have the strength to do so.

Part of what makes Pippi’s outsized strength so funny is its apparent impossibility. People can’t lift horses! And little girls definitely can’t. It’s not just the fact that horses are too big to lift (though apparently this guy lifts them) — it’s that little girls are too small and too weak to lift, well, anything, right?

The foil to Pippi Longstocking is the neighbor girl, Annika. While her brother Tommy is always more than eager to go along with Pippi’s plans, Annika isn’t so sure. She’s a well-behaved little girl who’s afraid of heights and doesn’t want to risk injury. When Pippi climbs inside a hollow tree, it takes some convincing for Annika to even brave the tree’s branches.

Annika is the stereotypical little girl. She’s too proper, too penned in, to ever lift a horse.

Pippi, meanwhile, is the little girl who breaks all stereotypes. Along with being strong, she’s outspoken, stubborn, and bold. She defies the control of adults of all shapes and sizes, speaks her mind, and mops floors her own way.

One might describe her as a feral child, but I’m more inclined to say that she simply hasn’t been broken by the expectations and impositions of broader society. Pippi is what little girls would be if they weren’t boxed in by the frailty myth, the idea that they shouldn’t, and indeed can’t, be strong and resilient and courageous.

I think that’s exactly why Pippi has had staying power.

Little girls on the whole have long been discouraged from embracing and expressing their physical power. Girls as young as 5 have concerns about their bodyweight2, while at the same age they’re already falling behind boys in both physical activity levels and enjoyment of physical activity3.

Pippi, on the other hand, displays the very things her peers have been denied: strength and self-assurance.

When she was first sharing the Pippi stories, the author Lindgren was blown away by how much the children in her life wanted to hear about Pippi.

“I felt as though this fantastical character must have hit a sore spot in their childish souls,” she told Svenska Dagbladet in early 1946. “I found the explanation later in Bertrand Russell, who observes in his book On Education, Especially in Early Childhood that the most prominent instinctive trait in childhood is the will to power. Children are tormented by their own weakness compared with older people, and want to be like them. That’s why normal childhood fantasies involve the will to power. … I don’t know if it’s true. I just know that all the children I’ve tried Pippi on clearly love hearing about a little girl who’s totally independent of all adults and always does precisely what she wants.”

For girls (and women), Pippi might just strike deeper. She represents an impossibility that speaks to our own untapped possibility. Her strongwoman antics — at the circus, with her horse, scrambling across the roof of Villa Villekulla — poke at an inner restlessness.

If Pippi is the strongest girl in the world, does that mean one of us is the second strongest?

All quotations of Astrid Lindgren are from her biography, Astrid Lindgren: The Woman Behind Pippi Longstocking by Jens Andersen, translated by Caroline Waight.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2548285/

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(19)30135-5/fulltext

Recommended Reading

Q&A with the author of American Girl’s 25-year-old The Care and Keeping of You body book for girls (Yahoo News)

The First Rule of Running After Childbirth Is That There Is No Rule (Outside)

What’s coming up?

Let’s redefine “athleticism”.