The 🍑 obsession is just another way aesthetics dominate women’s fitness culture

Enough with the butts, already.

I’ll be honest: I don’t really want to write about butts. I really don’t. I don’t understand the obsession that certain corners of the fitness community have with them, and I prefer to forget that some people ogle others’ behinds.

But … it would be a glaring omission to write about women and fitness without addressing the ever-present peach emoji. Between thong bathing suits and a particular athleisure trend that has women pulling their leggings up between their cheeks, we are all likely to be assaulted by someone’s booty just out there in the world. Call me a prude if you want, but I don’t think there’s anything remotely empowering about trends that draw others’ eyes to our backsides rather than our faces.

In this year of our Lord 2023, we can scan the horizon and see glute-focused workout routines aimed specifically at sizing up the derriere. We can see Kim K. (whom I personally don’t give a rip about) from miles away, with her figure surgically distorted to an extreme that makes Barbie look normal. We’ve got Brazilian butt lifts, leggings with extra padding back there — reminiscent of adolescent bra stuffing — and image after image on Instagram, Reddit, and TikTok of women and girls twisting backward to capture their buttocks in a gym mirror.

Not too long ago, in the early 2000s, girls like me didn’t want to have big butts. I remember laying on my stomach and craning my head around to see how big mine was and feeling a type of way at the fact that, to my eyes, it was big.

That wasn’t better than today’s obsession, but it was different. Or was it?

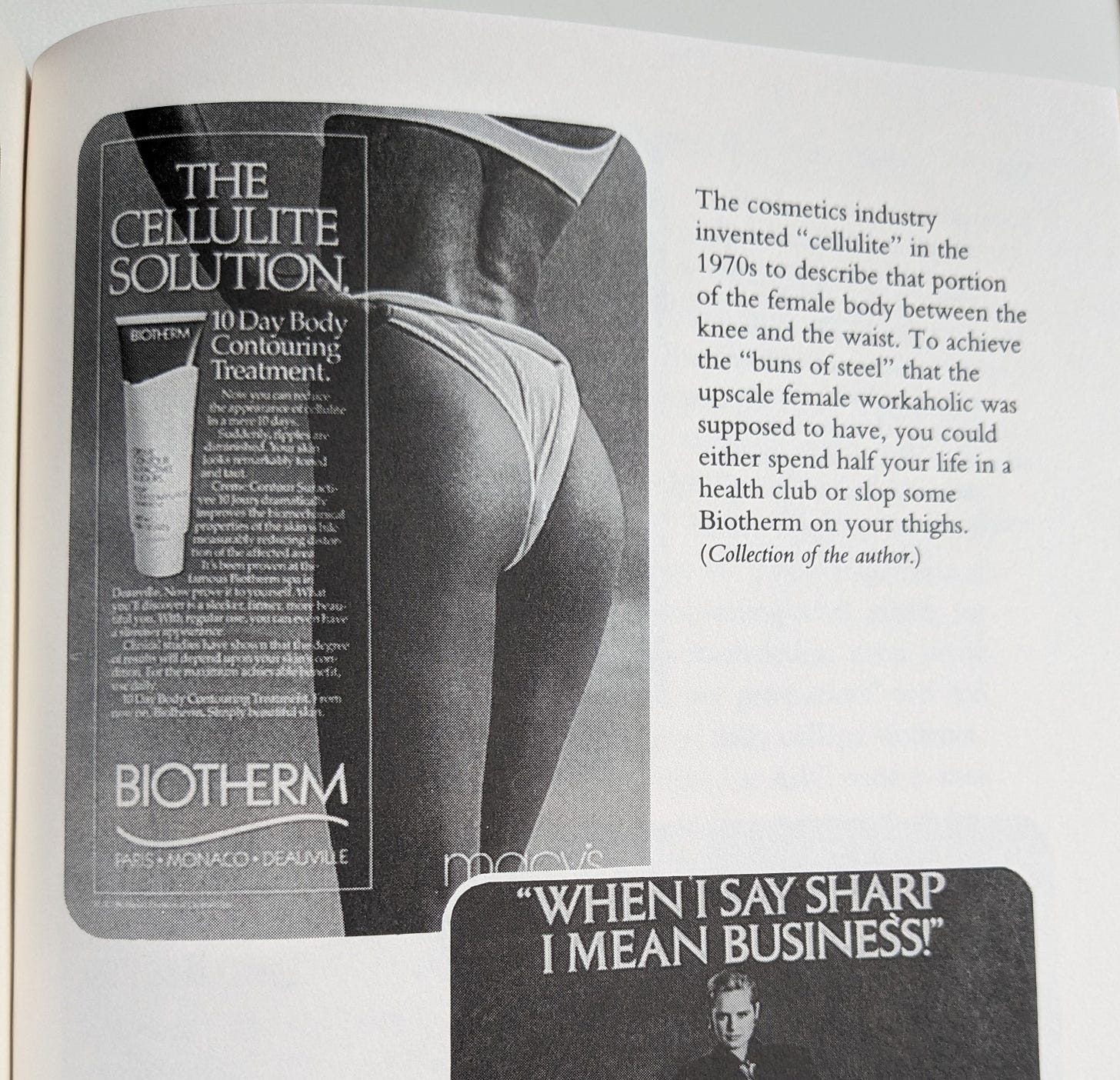

I recently read Where the Girls Are by Susan J. Douglas, a work of cultural history and criticism that holds a magnifying glass up to the messages promoted by the mass media in the 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s. It’s in the 80s that Douglas identifies an initial cultural fixation on women’s butts and thighs, with Buns of Steel, cellulite-smoothing potions, advertisements, and “bathing suits with legs cut up to just below the armpit” (a slight exaggeration) directing women’s attention to the site of perhaps our most inevitable curves.

“It was the slim, dimple-free buttock and thigh that became, in the 1980s and the 1990s, the ultimate signifier of female fitness, beauty, and character,” Douglas writes. And unlike breasts, which women could only enlarge through surgical means, butts and thighs could, ostensibly, be resized through mere effort. “This body part could be yoked to another pathology of the 1980s, the yuppie work ethic. Thin thighs and dimple-free buttocks became instant, automatic evidence of discipline, self-denial, and control.”

Is it a coincidence that this trend arose about the same time that women were embracing exercise on a large scale? (Jane Fonda’s first workout video released in 1982.) Douglas thinks not. Rather, the fixation stemmed from “the fitness craze” and could even be seen as a backlash against women embracing exercise for its physical and mental health benefits.

Of course, the goal in the 80s and 90s was a smaller butt — shapely, not flat, but also not fat, whatever that means. The outcome women were supposed to aim for did not look the same as today’s the bigger, the better booty.

But the way this functioned on a cultural level is practically identical.

If you were a woman who cared about her appearance and bought the messages ringing all around you (whether explicitly or implicitly), your butt became your project. And you could use everything from exercise regimens to diets to Biotherm contouring cream to make it tighter and tinier. Or at least, that’s how the messaging went.

The fact that women naturally carry more fat in their hips — and that this or that approach may not have the outcome promised because different bodies respond differently — was ignored.

“What made these thighs desirable was that, while they were fat-free, like men’s, they also resembled the thighs of adolescent girls,” Douglas writes.

“The ideal rump bore none of the marks of age, responsibility, work, or motherhood. And the crotch-splitting, cut-up-to-the-waistline, impossible-to-swim-in bathing suits featured in such publications as the loathsome Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue could never reveal that other marker of adulthood, pubic hair. So, under the guise of female fitness and empowerment, of control over her own body, was an idealized image that infantilized women, an image that kept women in their place. … The upper thigh thus became freighted with meaning. The work ethic, the ethos of production and achievement, self-denial and deferred gratification was united there with egoism, vanity, self-absorption, and other-directedness. With the work ethic moved from the workplace to the private sphere, the greatest female achievement became, ironically, her body, her self.”

Tell me if I’m wrong, but I’m pretty sure the peach emoji crowd is just as hung up on “egoism, vanity” and “self-absorption” in the quest for a bigger butt as our mothers, aunts, and maybe even grandmothers were in the quest for a tiny hiney. We’ve just swapped the contouring cream for five sets of heavy hip thrusts, followed by hundreds of lunges, glute raises, and split squats.

I will be the first to admit that I love all of those exercises. They’ve helped me recover from low back and hip dysfunction — and I even like how they make my butt look. But when the trend is all about appearances, all about attaining an aesthetic (which, by the way, depends more on your body type than your workout routine), we’ve set ourselves up for some mix of disappointment, frustration, and a never-ending quest for unattainable physical “perfection”.

Rather than chasing after pullups, handstands, pistol squats, a lifetime PR on the exercise of your choice, this obsessive trend directs us to focus again on aesthetics. Exercise is once more a means to an end, and the end, we hope, is visual perfection. It’s no longer about achievement, if it ever was. It’s about how big and round your buttcheeks look in intentionally wedged leggings or hanging out of an obscenely cut swimsuit.

I don’t know when the preferred aesthetic changed from the 80s, 90s, and early 2000s’ itty bitty booty to today’s cartoonified rump. I also don’t really care. It seems like cultural pendulums always swing to the extremes.

What I would like to know is why women keep falling for it — and what it would take for us to stop, opt out, ignore the butts in our faces (whatever they look like), and just live our lives without spending a fraction of a thought worried about how a dress or shorts or leggings make our butts look. This obsession is, well, asinine. And a waste of precious energy and brain space. We all deserve better.

Recommended Reading

Most Fitness Influencers Are Doing More Harm than Good (New York Times)

Female athletes face ‘serious health implications’ of missed periods (The Guardian)

What’s coming up:

Review of Christine Yu’s new book, Up to Speed: The Groundbreaking Science of Women Athletes

Like what you’ve read? Share Women’s Barbell Club with a friend!

Forward this email or share a link to our Substack page.

This describes exactly how I felt when I first joined the gym this year. I originally joined to help with my anxiety and for the physical benefits but I was bombarded by butts to the point where I had to ask myself if I should start focusing my workouts on that part of my body. Glad I didn’t give in and focused on the workouts that made me feel good!