“I’m not athletic.”

Every time a woman says these words, a gym fairy drops dead and I personally want to yell. I’ve heard some version of this statement from young moms, women in their late 20s, and probably high school friends if I think back long enough. But I’ve never believed it.

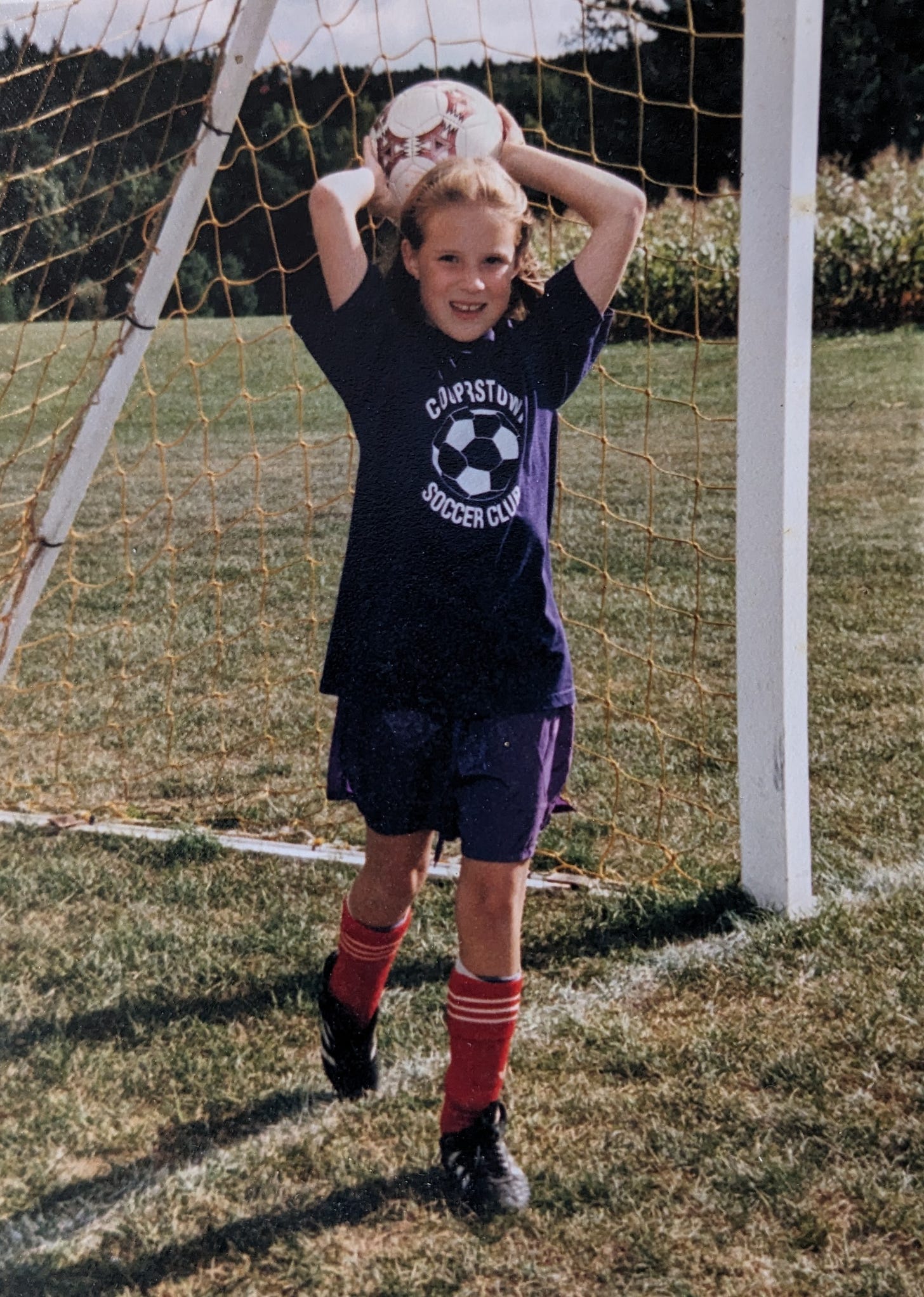

I started playing soccer in 2nd grade. For my first four years in the sport, I couldn’t figure out how to breathe when I ran. I’d get moving and instantly be struck by a side sticker, aka side stitch. I remember being on the purple team in 5th grade, running down the tree-lined field, and my side cramping up like someone had grabbed my right abdomen and started to squeeze. I slowed to a walk.

On the playground, I couldn’t swing from the monkey bars. I could barely hold on before my arms and my grip gave out. Instead of swinging, I’d jump to pull myself up and crawl across the top on my hands and knees.

Was I not athletic because 10-year-old me couldn’t run without cramping up? Was I unathletic because my arms were too skinny and weak to swing me from one end of the playground to the other?

A lot of us have this idea that athleticism is for other people, not us. We think because we don’t look a particular way, we’re not naturally coordinated, or we can’t do a standard pushup that we, by definition, are not athletic. We think because we were always picked last for kickball in elementary school that we’re inherently bad at all sporty things.

But what if I told you that athleticism is for everyone. That pushing your body to the limits — even if the limits aren’t impressive — is something you can do and is, by definition, expressing your athleticism?

What would it look like to adjust your working definition of athleticism to one that is accessible to everyone from little 10-year-old Meredith, huffing and puffing down the soccer field, to my 94-year-old grandmother who diligently goes to exercise class every week?

There are a few assumptions that get in the way of rewriting our definitions. Here are three I’ve run into the most:

Athleticism looks like XYZ.

Some people are cut out to be athletes, but not me.

Only elite competitors can claim to be “athletes”.

To help us all out, I’d like to address these assumptions one by one.

1. Athleticism is not a look.

In her book, Treating Athletes with Eating Disorders, clinical sport psychologist Kate Bennett points out that mass media broadcasts two consistent messages: “You need to be fit, and you need to look fit to be desirable, acceptable, and worthy in our society.”

But fitness is not a look.

This is the point that people like Bethany Robinson (aka Sporty Beth) are attempting to make online. While certain types of fitness will manifest in physical ways through the presence of muscle mass and improved circulation and heart function, those manifestations aren’t automatically shown in every fit person’s appearance. A fit person can have fat and be bigger than what is typically pictured as “fit”, and a skinny person can have terrible physical fitness.

“It is ironic that the general population defines fitness by appearance when the very definitions of fitness have nothing to do with aesthetics and instead reflect physical abilities and physiological adaptations,” Bennett writes. “The term ‘fitness’ has become a social construct, a money-making industry for many businesses, and a way to promote insecure sources of confidence through preoccupations with physical appearance.”

It’s high time we reclaim the term from its hijackers. If you can walk a flight of stairs without losing your breath, lift your bodyweight (or even half of it), stand on one foot for 20 seconds, do a backbend, or carry a toddler around, you have some level of physical fitness — and dare I say, athleticism — regardless of what you look like.

2. Athleticism is not a body type.

Related to the last point, but this is more about conceptions of athleticism than fitness. If you’ve ever heard the term athletic build thrown around in reference to women with more boxy frames, you know what I’m talking about.

In high school, one of my coworkers at McDonald’s randomly claimed that I wasn’t athletic. His comment caught me off-guard. He’d never seen me outside of work, much less in an athletic context, so how could he say that in such a matter-of-fact way?

At this point, I’d learned how to breathe while running and routinely ran sprints for fun. I played co-ed soccer and outran my male peers. My mom says our family has “legs like trees” and I was happy about that fact. Being an athlete was a core part of my identity.

But I was skinny on my upper half. I had a small waist, not that boxy “athletic build”. Maybe that’s what my coworker was getting his ideas from? My body type?

Let’s be abundantly clear: you don’t have to have a particular type of body to be an athlete. You just need your body. And none of us can judge a person’s athletic abilities based solely on their appearance. Let’s stop doing this — to others and ourselves.

3. Athleticism is not reserved for the elite.

One of my favorite things about the CrossFit community is how gyms refer to their members as athletes. Regardless of age, regardless of ability, regardless of achievement. If someone walks through the doors with the intention of working out, that person is an athlete.

While many CrossFitters come from a sport background, there are plenty who don’t. This might be the first time they’ve ever been referred to as an athlete, as well as the first time that they’ve been encouraged to attempt more intimidating movements, like pullups, rope climbs, box jumps, or the ever-intimidating snatch.

Here’s the truth: Before you step into an athletic setting, even without years of training and practice, you already have innate athletic ability. Don’t believe me? Look at toddlers. They’re training every day, pulling themselves up on furniture, taking shaky steps. Their little muscles are working hard to build strength and coordination.

You may not remember, but you were a toddler once. And that inner drive to try harder, again and again and again, to find your balance, increase your strength, explore a new type of movement — that’s still inside you somewhere. Give it a chance, and it might just wake up and surprise you.

Of course, there are levels of athleticism. Simone Biles and Usain Bolt are legitimately in leagues of their own. But elite levels of athleticism do not cancel out the physical capacities of those of us who are more ordinary athletes. Just because an everyday person cannot win 23 Olympic gold medals, run the 100-meter in 9.58 seconds, or deadlift 400 pounds does not mean that what they can do (now or in the future) is unathletic.

We all have athletic capacity, and that capacity deserves to be explored and expressed.

So what definition of athleticism am I proposing?

Simply, the capacity (and decision) to face and endure physical strain through a variety of challenges that demand any combination of endurance, strength, agility, power, stability, coordination, and flexibility.

If you challenge yourself in any of those ways on a regular basis, congratulations — you are an athlete.

Recommended Reading

Bookmark This Daily Stretching Routine for Better Flexibility and Mobility (Real Simple)

Test Your Exercise I.Q. (New York Times)

Why Do I Get Out of Breath Walking Up Stairs If I’m in Good Shape? (Shape)

What’s coming up?

How to get — and stay — motivated.